A few weeks ago as I was leading my martial arts class in a local park, one of my students said to me, “I just saw a friend walk by and I know he’s going to ask me later what I was doing here. I’m not sure what I should tell him. What are we learning here? What is this class called?”

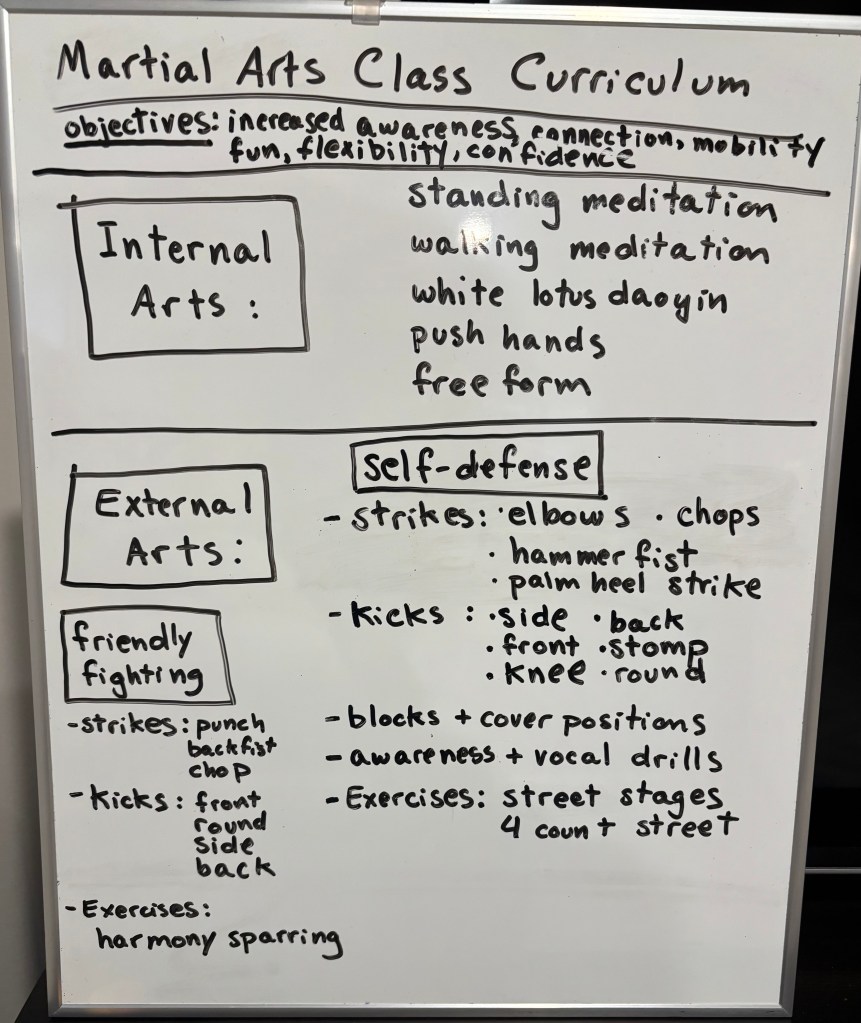

Her question shocked and delighted me–she had been in my class for months and after all that time she was asking me what the class actually was. She asked for words that described what we were doing. I stammered for an answer. “Umm, well, it’s called Women’s+ Martial Arts, and we’re learning martial arts, but not in a traditional sense. We’re training some internal arts, but also some external. And some self-defense… I think you should tell your friend it’s a martial arts movement class.” I felt pretty good about my answer, but didn’t feel like it was entirely complete. I told her after class that I appreciated her question and would continue to think on it. I told her I would also start writing out our curriculum so we could all get a clearer sense of what we were learning.

My big takeaway, though, was that I needed to answer a simple, foundational question for myself and my students: What are we doing here?

I’ve been thinking about my answer ever since, and I have been thinking about how important her question was. Clarifying what we are learning and why is an important task for a teacher who wants to have good communication with her students.

I started by writing out a rough curriculum of what we practice in class:

Writing this out also helped me notice my goals for our class. In my younger days, my goals as a martial artist were much different than they are now. Back then I wanted to be tough and strong. I wanted to be a formidable fighter, win at tournaments, and get my black belt. But I also wanted to be part of a martial arts community in which we were doing internal work to become our best selves. I felt like I had all of those things for a while in my Mo Duk Pai days, but after having a baby, everything changed.

I had worked so hard to become tough and strong, but after having my son, my body was stretchy and weak. I couldn’t train as hard as I used to, but my training partners still hit me as hard as they had before. They hit me too hard, and unfortunately the culture in the school was such that I didn’t feel safe speaking up and telling my fellow students to go easier on me. That would’ve been showing too much weakness. And so, because I was afraid of getting seriously injured in training, I left Mo Duk Pai.

When I returned to martial arts with a new teacher a few years later, I started noticing how toxic and subtly sexist the culture had been in my old school. I realized that I no longer wanted to buy in to the notion of trying to be the toughest kitty in the class. I wanted to move my body joyfully and be healthy and injury-free.

My goals for my students now are informed by these past experiences. Most of all, I want my students to feel their own embodiment. I want them to notice the messages their bodies are sending them, and I want them to practice listening to their own selves. I want them to be confident and strong, but I want their strength to come from sensitivity and awareness, not toughness. I want them to know themselves well, and to have the courage to speak their own truths. I also want us to have a joyful, vibrant community based on respect and our shared personal growth.

The moves we practice are all vehicles for working on these deeper issues. Our internal arts practices allow for deep listening inside of ourselves, while our external practices help us in setting and maintaining healthy boundaries. We practice moving martially to defend ourselves, but also to keep our bodies flexible and agile as we age.

So, the core of what I teach is embodiment, mindfulness, and standing up for ourselves. In this sense, martial arts is simply the context for working on a deeper connection with ourselves and each other.